The great church father Jerome once declared:

“Five gospels record the

life of Jesus. Four you will find in books and the one you will find in the

land they call Holy. Read the fifth gospel and the world of the four will open

to you.”

Jerome’s adage should

receive canonization status. As one cannot effectively play chess without a

board, so it is when reading the Bible without a strong familiarity of the

physical contours of Israel.

The geography of Israel

acts as a hidden character throughout the corpus of the Bible; its personality

silhouettes the stories in the OT and NT. Woven through the Biblical text,

primarily in the OT, is a sub-narrative centered around a neo-trinitarian thread:

God, people, and land. [1]

God created man from

soil. God granted real estate to a nascent people group to inhabit. Emotionally

charged Scriptures comment on the alienation of being exiled from one’s

homeland. Modern conflicts between Israelis and Palestinians stem from an

intense terra-centric ideology.

Land tethers us to this

Earth, informs our worldview, and functions as an identity marker. We tread

upon it every day of our lives without paying respect to its ownership over us.

It dramatically

influences who people become by impacting the psychosocial faculties. We could

say the tangible soil blanketing his planet fertilizes the intellectual soil of

our psychology.

Even Jesus was

submissive to this “law of the land.”

The Gospels claim Jesus

grew up in Nazareth. Now the largest city in the northern district of Israel,

the Jewish historian and native Galilean, Josephus, neglects to even mention it

perhaps indicating its irrelevance in the Galilee region during the 1st A.D.

Remotely couched in a geological bowl in the hills of Lower Galilee, no major

road passed through this hamlet. Nazareth’s view of the surrounding countryside

is obstructed to a large degree by the basin’s rims which act as the horizon

line. But once one ascends the southern edge of the depression and crests the

ridge, the view is nothing less than panoramic. Colloquially called “Nazareth

Ridge” but formally accepted as Mt. Precipice, the 1879 ft lookout affords a

view 30 miles in three cardinal directions (South, West, and East) across the

expansive Jezreel Valley.

|

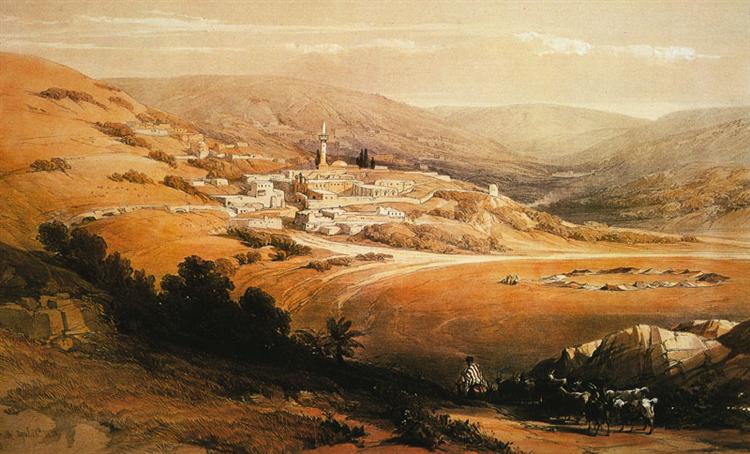

| View of Nazareth Ridge in the distance. Courtesy Matson Collection. |

Peering down from atop the Nazareth Ridge over the Jezreel Valley blanketed with rich alluvial soil (330 feet deep in some spots), a dichotomized view comes into focus: the open expanse of agricultural surplus in the valley vs. the agronomic dearth of Nazareth. Seven major highways passed through this valley. It was an international economic turnstile throughout Israel’s history and no different in 1st A.D.

But for a young astute

Jewish student of Scripture such as Jesus who invariably frequented this

lookout with his neighborhood friends, the Jezreel Valley charts a map of OT

stories laden with heroic tales of “saviors” who intervened to rescue their

fellow constituents from oppressive enemies, anointed kings with political

aspirations to exert hegemony in the region, and devoted prophets speaking on

behalf of God with miracles on their resume.

To the west on the Mt.

Carmel Mountain range, YHWH displayed his predilection for pyrotechnics as

Elijah hurled insults at the impotent Syrian storm/fertility god, Baal. Further

down the Carmel Range, the prized city of Megiddo, whom Thutmose III boasted

“…is like capturing 1000 cities.” Ahaziah, sixth king of Judah, became a

casualty at the hands of Jehu the usurper and died there. Josiah, the

avant-garde religious reformer, tragically died at the hands of Pharoah Neco at

Megiddo.

To the south, Saul and

Jonathan lost their lives in battle against the Philistines on Mt. Gilboa.

Their heads were decapitated, and bodies unceremoniously hung on the wall of

Beth-She’an down the slope. Also, to the south at Tel Jezreel, the winter palace

residence of the Omride dynasty where Jezebel manipulated Ahab into murderously

confiscating Naboth’s vineyard and because of it reaped the invective death

sentence of Elijah. Several years later, Jehu staged a coup at the behest of

YHWH. He furiously drove his chariot into the Jezreel Valley from Gilead and

executed Elijah’s oracle; Jezebel was thrown from the window of the palace,

trampled by chariot horses, and her blood lapped up by dogs. Jehoram,

recovering from wounds sustained in battle, was also assassinated by Jehu and

his body disposed of in Naboth’s vineyard adjacent to the palace. A short jaunt

from Jezreel lies the Harod Spring where Gideon encamped against the Midianites

and separated the men from the dogs.

On Mt. Tabor to the

east, Deborah and Barak assembled an army to defeat the chariot forces of

Sisera in the Jezreel Valley. About 50 years before Jesus’ birth, a rabble

rouser by the name of Alexander, the son of a Hasmonean noble, incited a series

of uprisings against Rome and was eventually defeated at Mt. Tabor. Mt. Moreh

protrudes near the center of the valley and preserves the memory of Elisha’s

resuscitation of a dead boy in the village of Shunem on the south side of the

mountain. On the opposite side of Mt. Moreh lies Nain, the village where Jesus

followed in Elisha’s footsteps. He also revived an unnamed widow’s deceased

son. Near Nain, Saul consulted the medium at En-Dor hoping to gain a tactical

edge over the Philistines but instead provoked Samuel to anger after waking him

from his death sleep. Ophrah, modern day Afula, is positioned almost in the

center of the valley and was probably home to the great military liberator

leader Gideon.

And that’s just from the

southern vista of Nazareth Ridge.

Ascension out of the

bowl to the northern ridge and a meager four miles NW sat Sepphoris, a

strategically located city Herod the Great captured in a snowstorm in 39-38

B.C. Coined the “ornament of Galilee,” it served as the capital until the

construction of Tiberias circa 20 AD and preserves the memories of a

rebel named Judas who led the citizens in a revolt circa 6 AD due to a census

issued for tax purposes. In response, the Roman governor Varus dispatched some

of his legions to extinguish the flames. Instead, he ignited tensions and

subsequently reduced the city to ashes. The ~10 year old Jesus may have watched

the city burn perched atop the northern ridge. And three miles north lay the

scanty village of Gath-Hepher, home of Jonah the prophet. No wonder Jesus

connects himself with Jonah on a few occasions. He was also a prophet to

Gentiles but seemed to be rejected as a legitimate diviner by the aristocracy

of Jerusalem on geographic grounds; a prejudice Jesus also felt (John 7:52).

All these Biblical

stories and current events sat within eyeshot of Jesus conjuring up the rich

but violent history of his ancestors. Arguably, the contemporary turbulence he

witnessed (see Sepphoris conflagration) created a visceral reproduction of his inherited

bellicose traditions the Jezreel Valley retained.

The unmet expectations

of OT heroes must have ruminated in his mind. The saviors of Judges and the

kings of Israel and Judah all were to some degree designated messiahs chosen by

God to promote a global awareness of the true God. They were to circulate the

teachings of God, not just to their own constituency but also foreigners

constantly passing through this “land between” imperial empires. Their fidelity

to God in a pantheistic charged cultic environment would separate Israel and

Judah from their neighbors and put on full display the distinctive character of

God as a benevolent deity; a celestial concept so far removed from religious

mainstream thought as is the east from the west.

But Jesus’ recollection

of the past wasn’t the only force he felt.

Below Jesus’ feet, the

bounty of a prosperous life as the traffic of the ancient world flowed through

the Valley. The Samaria Hills to the south housed the road to Jerusalem,

teeming with pilgrims and merchants from Egypt. Arab caravans originating in the

remote wastelands of Jordan entered the fords of the Jordan River carrying an

array of exotic goods from the Orient. A major artery from Damascus in the

north skirted the foot of Nazareth Ridge, meandering through the valley. Ships

from the western Mediterranean walked upon the waters of the sea’s vast expanse

hauling expensive imported cargo sucked up at the port of Ptolemais, easily

seen from the northern ridge. Legions of Roman soldiers carrying their

respective standards and politicians escorted by their entourages landed at

this port, traversing the roads around and through the valley. The rumors and

scandals of the Herodian family reverberated along these roads. The latest news

of proclamations by Caesar and pronouncements by the Senate were on the lips of

those travelling nearby. Revolts in other parts of the Roman empire surely made

their way into conversation amongst a Jewish population bent on reestablishing

their national independence, a circumstance they experienced only ~100 years

earlier under the Hasmoneans. The rhetoric of Roman politicking and burdensome

news of tax rates all must have fallen on the ears of the youthful Jesus.[2]

The sirens of the finer

things of life sang their tune while passing through. The melody of the medley

of options must have been a struggle to resist growing up in a resource-poor

town. The alluring scent of opportunity and intoxicating profusion of commercial

affluence must have tugged at the spirit of Jesus.

All the world had to

offer lay crouched at Jesus doorstep.

Yet, he did not take the

bait.

The external forces

pulling at Him from multiple angles provided every justification to jettison

the call on His life. He waited until “the time had fully come”, submitting to

God’s will and not the temptations of earthly pursuit. Sometimes, what Jesus did

NOT do is equally important, if not more illustrative, than what he did do.

As Jesus peered out over

this valley marked by blood, violence, death, disappointment, and war,

habitually overrun by greater foreign powers, he too may have questioned his

inherent identity and how he fit into the narrative of his people. The

arrowhead shape of the valley itself personifies its tumultuous history as a

war-torn region.

Perhaps he asked himself

the following questions:

How am I to function as

Messiah, given all the failed attempts by my ancestors?

Do I follow suit and

attempt to usher in the Kingdom of God by force as my OT protagonists did or

like the Romans do?

Shunning the ancient war

paths blazed by his ancestors, Jesus opted to pursue the road less travelled.

He refused to repeat his “family” history or replicate the actions of his

fathers.

The aspirations of his

predecessors and contemporaries hinged on political maneuvering, nationalistic

hopes, and expansion of the land through force.

Jesus employed a more

anthropological approach.

His talking points

emphasized right relationship between God and neighbor, internal

self-awareness, and spaciousness of the heart.

The Jezreel Valley was a

psychological crucible, so to speak, for Jesus; a spiritual crossroads he

undoubtedly wrestled with as “he grew in wisdom and stature and in favor with

men.”

The confluence of past

and present of the Jezreel Valley was instructive to Jesus’ singularity and how

He chose to live it out. Exploits and adventures of past celebrated Biblical

characters clashed with the intrigues and promise of the 1st AD

present, creating a battlefield of ideas. Though the Jezreel Valley retains

memories of physical wars, Jesus’ conflict was internal.

Only though interfacing

with the geography of Jesus’ hometown can we arrive at such conclusions. If God

is the consummate teacher, then His selection of this land is His curriculum.

The English word Jezreel is a translation of two Hebrew words meaning “God

sows.” And He certainly was sowing something in Jesus in his formative years.

[1] I am indebted to my teacher, Dr. Paul Wright, who

provided this astute insight pertaining to the overall arc of the Biblical

narrative.

[2] This paragraph is an adaptation of George Adam

Smith’s seminal work. Smith, George Adam. 1920. 4th Edition, The

Historical Geography of the Holy Land, Especially in Relation to the History of

Israel and of the Early Church. Pages 433-434. New York, George H. Doran

company.